Musée de l'Orangerie. Impressionism

Musée de l'Orangerie is the third third impressionist museum in Paris with Musée d'Orsay and Musée Marmottan. Set in Les Tuileries Gardens, it displays the Water Lilies by Claude Monet and the rich Walter Guillaume impressionist collection. An intimate museum centrally located and a good alternative to the crowded Musée d'Orsay. Paris Museums.

Impressionism in Orangerie

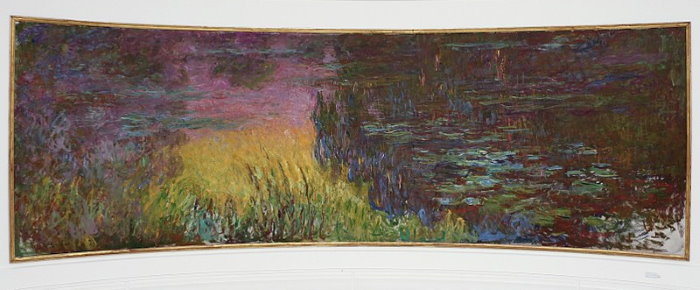

Located across the Seine River from Musée d'Orsay, the Musée de l’Orangerie is known for Claude Monet’s monumental series of water lily paintings, Les Nymphéas. The panels are displayed as the artist intended, from floor to ceiling inside two large oval shaped rooms, and bathed in the natural light from two large skylights. The museum also houses the first class Walter Guillaume collection of impressionist paintings and early 20th century art including Picasso, Modigliani, Soutine, and Braque.

Paris 75001 France

Oopen Monday, Wenesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday. 9am to 6pm. Closed: Tuesdays, May 1st & December 25th. Tickets: 12.50 euros.

Coco Chanel - Marie Laurencin - Orangerie

The Walter Guillaume collection

The Walter Guillaume collection, displayed in Musée de l'Orangerie, comprises 146 works collected for the most part by Paul Guillaume, a French art dealer. From 1914 until his death in 1934, he amassed a first class collection, from Impressionism to Modern Art, along with pieces of African art. After his death, his widow Domenica, remarried to the architect Jean Walter, transformed and reduced the collection while also making new acquisitions. She wanted to name the collection after both her husbands when the French State acquired it in the late 1950s.

From then on, the collection was destined for display at the Musée de l'Orangerie. It comprises 25 works by Renoir, 15 by Cézanne, 1 each by Gauguin, Monet and Sisley, all from the Impressionist period. From the 20th century, the museum boasts 12 works by Picasso, 10 by Matisse, 5 by Modigliani, 5 by Marie Laurencin, 9 by Douanier Rousseau, 29 by Derain, 10 by Utrillo, 22 by Soutine and 1 by Van Dongen.

Paul Guillaume - Modigliani - Musée de l'Orangerie

The Walter Guillaume collection detailed history

From humble beginnings, Paul Guillaume (1891–1934) rose to become one of the leading cultural players and art dealer-collectors of Paris in the early twentieth century. Guillaume died at the age of forty-two, by which time he had amassed an outstanding private collection of works by leading modernists. Unlike many art collectors of the time, Guillaume did not come from a wealthy and cultivated background, nor was he only interested in simply supplying works of art for customer demand like other art dealers. He also actively promoted certain aspects of the artistic and cultural life of Paris, providing moral and material support to artists, and interpreting the art of his time for his contemporaries. This approach, while not uncommon today, was innovative at the time and had previously been attempted by only a few courageous dealer-collectors in Paris, such as Paul Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard. Guillaume was celebrated by the artists whom he supported; for instance in Modigliani's portrait the words Novo Pilota, or ‘new helmsman’, identify the sitter as being at the forefront of modern art. Guillaume's premature death prevented his dream – of transforming his private collection to a museum of modern art – from being realised. After his death Domenica, his widow and heir, remarried and modified the existing collection, selling some of the more extreme avant-garde works (and later his collection of African art and modern sculpture) and acquiring works of a more conservative character. Domenica's concern to promote harmony among the works in the Guillaume collection made her edited version of the collection all the more typically a capsule of Parisian taste in the 1920s. Before he died, Paul Guillaume had resolved to give his collection to the Louvre. Domenica, a lover of Impressionist art (Monet's Argenteuil 1875 was one of her last acquisitions), sought to intertwine her late husband's philanthropic impulses with her own. After much negotiation, the French state acquired the collection in two consignments in 1959 and 1963 and housed it in the refurbished Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris, which was at the time attached to the Louvre for administrative purposes. The Orangerie now housed not only Monet's major Water Lilies cycle of paintings, but also the magnificent collection bearing the names of Domenica's two husbands, Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume. The collection has been on permanent display since 1984.

History of l'Orangerie

The Musée de l'Orangerie is housed in an old orangery, built in 1852 to house the tangy citrus fruits of the Tuileries garden in winter. Like all orangeries, the stone building was designed in length, and was glazed on the Seine side and walled up on the garden side in order to keep the heat of the building as much as possible. Its rather classic and understated decor blends in perfectly with the surrounding neighborhood. Transformed from the end of the 19th century until the beginning of the 20th century into a warehouse, accommodation for soldiers, then a place for various events, the old orangery finally fell into the hands of the administration of the Beaux-arts in 1921, wishing to house an annex to the Musée du Luxembourg, at the time the National Museum of Modern Art. Chosen to furnish the interior of the building, Claude Monet produced a superb wall set which he named the Water Lilies cycle and which he donated to France. The museum was open in 1927.

Musée de l'Orangerie entrance

Portrait de deux fillettes - 1892 - Auguste Renoir - Musée de l'Orangerie

Musée de l'Orangerie apartment and hotel map

Waterlilies - 1919 - Claude Monet - Musée de l'Orangerie

Detailed history of the Waterlilies in Musée de l'Orangerie

Offered to the French State by the painter Claude Monet on the day that followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918 as a symbol for peace, the Water Lilies are installed according to plan at the Orangerie Museum in 1927, a few months after his death. This unique set, a true "Sixtine of Impressionism", in the words of André Masson in 1952, testifies to Monet’s later work. It was designed as a real environment and crowns the Water Lilies cycle begun nearly thirty years before. The set is one of the largest monumental achievements of early twentieth century painting. The dimensions and the area covered by the paint surrounds and encompasses the viewer on nearly one hundred linear meters which unfold a landscape dotted with water lilies water, willow branches, tree and cloud reflections, giving the "illusion of an endless whole, of a wave with no horizon and no shore" in the words of Monet. This unique masterpiece has no equivalent worldwide. The Nymphéas [Water Lilies] cycle occupied Claude / Monet for three decades, from the late 1890s until his death in 1926, at the age of 86. This series was inspired by the water garden that he created at his Giverny estate in Normandy. It resulted in the final great panels donated by Monet to the French State in 1922, and which have been on display at the Musée de l’Orangerie since 1927. The word nymphéa comes from the Greek word numphé, meaning nymph, which takes its name from the Classical myth that attributes the birth of the flower to a nymph who was dying of love for Hercules. In fact, it is also a scientific term for a water lily. The famous water lily pond inspired Monet to create a colossal work composed of almost 300 paintings, over 40 of which were large format. Three tapestries were also woven from the Nymphéas paintings, thus affirming the decorative nature of these series. Two types of composition were defined by the artist at the beginning of the cycle. The first includes the edge of the pond and its dense vegetation: that is seen in the Bassins aux nymphéas of 1899-1900 [Water Lily Pond], then in the Pont japonais [Japanese Bridge] from the later years. The second, in contrast, plays on the emptiness, and includes only the surface of the water with flowers and reflections interspersed. This is seen in the Paysages d'eau [Water Landscapes] (1903-1908), close-ups in a tightly framed composition, organised in series, in which each element is presented as a fragment. This composition is also, and above all, a wall decoration. Although the idea for the project to create a circular series of decorative paintings had been taking shape since 1897, it was in 1914 that the painter decided henceforth to put all his energies into producing his "great decoration". This one took its final form in the arrangement in the Orangerie: a panoramic frieze laid out almost seamlessly, and enveloping the viewer in two elliptical rooms. It was in 1914, at the age of 74, when he had just lost his son and could see no hope for the future, that Monet felt a renewed desire to "undertake something on a grand scale" based on "old attempts". In 1909, he had already told Gustave Geffroy that he wanted to see the theme of the water lilies "carried along the walls". In June 1914, he wrote that he was "embarking on a great project". This undertaking absorbed him for several years during which he was beset by obstacles and doubts, and when the friendship and support of one man proved decisive. This was the politician Georges Clemenceau. They met in 1860, lost touch, and met up again after 1908 when Clemenceau bought a property in Bernouville near Giverny. Monet shared Clemenceau Republican’s ideas, and we also know of Clemenceau’s keen interest in the arts. During the war, Monet continued his work alternately in the open air, when the weather was suitable, and in the huge studio that he had had built in 1916 with roof windows for natural light. On 12 November 1918, the day after the Armistice, Monet wrote to Georges Clemenceau: "I am on the verge of finishing two decorative panels which I want to sign on Victory day, and am writing to ask you if they could be offered to the State with you acting as intermediary." The painter, therefore, intended to give the nation a real monument to peace. At this time, when it was still not certain where the decorative series was destined, it seems that Clemenceau managed to persuade Monet to increase this gift from just two panels to the whole decorative series. In 1920, the gift became official and resulted, in September, in an agreement between Monet and Paul Léon, director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, for the gift to the State of twelve decorative panels that Léon would undertake to install according to the painter’s instructions in a specific building. However, Monet, prey to doubt, continually reworked his panels and even destroyed some. The contract was signed on 12 April 1922 for the gift of 19 panels, but Monet, still dissatisfied, wanted more time to perfect his work. Clemenceau wrote to him in vain that year "you are well aware that you have reached the limit of what can be achieved with power of the brush and of the mind." But, in the end, Monet would keep the paintings until his death in 1926. His friend Clemenceau then put everything into action to inaugurate the rooms for the Water Lilies in strict accordance with Monet’s wishes. The Musée de l’Orangerie houses 8 of the great Nymphéas [Water Lilies] compositions by Monet created from various panels assembled side by side. These compositions are all the same height (1,97m) but differ in length so that they could be hung across the curved walls of two egg-shaped rooms. The artist left nothing to chance with this set of paintings that he had long pondered over and that were displayed according to his wishes in conjunction with the architect Camille Lefèvre and with the help of Clemenceau. He planned out the forms, volumes, positioning, rhythm and the spaces between the various panels, the unguided experience of the visitor through several entrances to the room, the daylight coming in from above that floods the space when the sun is out or which is more discreet when the sun is masked by clouds, thus making the paintings resonate according to the weather... The whole set is one of the most vast and monumental creations in painting made in the first half of the 20th century and covers a surface area of 200m2. The dimensions and area covered by the painting envelop the viewer in over nearly 100 linear metres, where a landscape of water punctuated with water lilies, willow branches, reflections of trees and clouds unfolds, creating "the illusion of an endless whole, of a wave with no horizon and no shore" as Monet put it. The paintings and their layout echo in the orientation of the building, as the placement of scenes with sunrise hues are to the east and those with hues of the sunset are to the west. Thus, the representation of a continuum in time and space is materialised. In an equally suggestive way, the elliptical shape of the rooms draws out the mathematical symbol for infinity. The Water Lilies paintings at the Musée de l'Orangerie have sometimes had to contend with various events and happenings. In particular, the roof of the second room was damaged during the 1944 bombings as well as one of the compositions, while the other panels remained miraculously unharmed. The 2006 renovation was also the chance to restore the Water Lilies room to its original state, a state that had been lost during the renovation work done in the 1960s that obstructed the natural light Monet had wanted.